Media Release

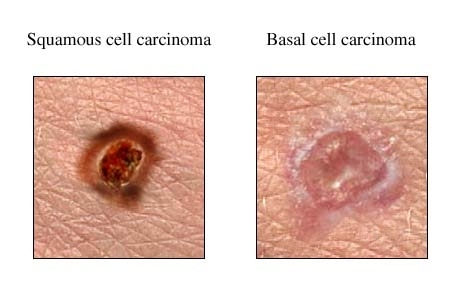

From: QIMR Berghofer Medical Research InstituteAn Australian study has discovered 45 new genetic variants that put people at a greater risk of developing the most common form of skin cancers, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

The research by scientists at QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute more than doubles the genetic information now available on these cancers.

Skin cancer is a major burden in Australia and in populations around the world with European ancestry.

Direct Medicare costs in Australia for BCC and SCC exceed $100 million, with the total associated costs including diagnosis, treatment and pathology exceeding $700 million, making these Australia’s most costly cancer.

Due to their sheer numbers, the exact number of new cases of SCC and BCC is unknown, but the number diagnosed is more than all other cancers combined.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates 714 people will die as a result of BCCs and SCCs in 2019.

Study senior author and the head of QIMR Berghofer’s Statistical Genetics group, Associate Professor Stuart MacGregor, said researchers examined data from 48,000 people who were treated for BCCs and/or SCCs in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

“We compared the genetic information of patients treated for BCCs and SCCs to that from 600,000 people without these cancers – which allowed us to identify which genes were different between the two groups,” Associate Professor MacGregor said.

“We identified 45 new genes which had not previously been linked to these cancers. Most affected both BCCs and SCCs, although a few were specific to one or the other. Previously only about 40 genetic variants for these skin cancers had ever been identified.

“While solar ultra violet radiation exposure is the biggest risk factor for developing skin cancers, this study shows there are important inherited contributions underlying BCCs and SCCs.”

Lead researcher, Dr Upekha Liyanage, said the discovery of new genetic variants may help to explain why some people developed these skin cancers, while others who may have similar features, such as pale skin or freckles, did not.

“On the flip side, although the study looked only at the genetic information of light skinned people, identification of genetic markers could also explain why some people with darker skin types still get BCCs and SCCs,” Dr Liyanage said.

“Currently there’s no genetic testing for skin cancers, but if we can get a clearer understanding of which genes are responsible and where on the DNA these genes are located, other scientists can start working on finding better treatments and preventative strategies.

“This research, which is the largest study to date into the genetic variants influencing BCCs and SCCs, is also valuable because it could be used to repurpose drugs that have already been approved for some conditions or that are under clinical trial, to speed up treatment options.”

The researchers said while the genetic discovery was a significant step in understanding these skin cancers, it was important for the community to remember that ultraviolet exposure was still the single biggest cause of skin cancers and people should continue to be sun smart by slipping on protective clothing, slopping on SPF30 or higher broad spectrum, water resistant sunscreen, slapping on a broad-brimmed hat, seeking shade and sliding on sunglasses.

The study findings are published in Human Molecular Genetics.

The research was funded by The National Health and Medical Research Council.

Quick Facts:

· Collectively BCC and SCC are known as non-melanoma skin cancers, although the term keratinocyte cancers is preferred; “non-melanoma” suggests they are trivial when in fact their impact is enormous (higher cost than any other cancer in Australia).

· In 2014, almost 1 million Medicare benefits claims were paid for SCCs and BCCs, totalling $127.6 million.

· AIHW data for 2013–14 also shows 114,722 people were hospitalised in Australia for non-melanoma skin cancer-related issues, a 39% rise from 2002–03 (82,431).

· The World Health Organization (WHO) says between two and three million non-melanoma skin cancers occur globally each year.

· The US based Cancer.Net says about 2,000 people die from basal cell and squamous cell skin cancer in that country each year.

AIHW statistics are available in the Cancer in Australia 2019 report. Total cost of non-melanoma skin cancers: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2012/197/10/non-melanoma-skin-cancer-australia